The moment Miho Inagi decided she would open an authentic New York-style bagel shop in Tokyo, she burst into tears – tears of excitement. But as she collected herself a few minutes later, she realised there was a major problem with her plan: she had no idea how to bake. “Ideas were rushing through my head. I just had this very clear vision of what I was going to do,” she recalls. “But I knew I had a hard road ahead of me. Because I’d never even baked a loaf of bread.” Inagi’s epiphany came in 1999, when she was celebrating her graduation with a holiday in New York. At Manhattan institution Ess-a-Bagel, she ordered a pumpernickel bagel with a filling of Spanish eggplant salad. “I just thought ‘what’s that weird brown one?’” Inagi recalls. ‘As soon as I tasted it I fell in love. It was so different from what I’d had in Tokyo, I began to wonder whether bagel makers in Japan had ever eaten the real deal.” Inagi befriended Ess-a-Bagel’s owners, the late Eugene and Florence Wilpon. They promised that if she came back the following year, they’d put her to work in the store. “I don’t think they really believed I would do it,” she says. Twelve months later, having quit her Tokyo desk job, she was back and ready to learn the art of making a bagel. First she manned the takeout counter, where she mastered how to sling a bagel – and speak like a New Yorker. Later she worked in the kitchen, learning how to roll, boil and bake like a pro. The name Maruichi Bagel loosely translates as ‘Number One Bagel’, with maru meaning ‘circle’, after the shape of the shop’s main event. The business came to life in 2004 in tiny premises in a smart western suburb, later moving to its current location in a converted garage in Shirokane. At lunchtimes and on weekends, customers wait patiently in a line down the street. “Eugene and Florence always told me that I shouldn’t expect to replicate their bagels exactly, and that I should take advantage of local ingredients and flavours to create my own style,” says Inagi. So Maruichi sells both New York-style classics such as ‘Sesame’ or ‘Everything’ bagels, and newer recipes like ‘Caraway Raisin’ or ‘7-Grain Honey Fig’. The kitchen also makes ‘bagelwiches’ to order, loading them with fillings like pumpkin, sweet potato and bean salad, vegetables and olives, all alongside smoked salmon, prosciutto and – of course – varieties of cream cheese. Hand-rolling the dough creates its signature dense-yet-tender texture, and boiling it gives the crust its distinctive crunch – these things, as well as the baking, are done by a core team of kitchen staff. But to this day it’s Inagi who crafts the dough. “It’s the key to every good bagel,” she says. “Making it consistent, day in and day out? That’s my job.”

Ginza Motoji

Koumei Motoji learned the hard way that first impressions count. During a visit to Paris many years ago, he entered a bistro for lunch. He was as fashionably dressed as any typical Parisian. “But I’m Japanese,” he says. “So I was ushered to the back like I was an embarrassment.” The next day he returned to the same restaurant wearing a kimono, “and they treated me like a rock star.” Motoji grew up on the island of Amami Oshima in southern Japan, a place famous for its high-quality silk. He recalls the day his mother gave him a kimono that had belonged to his late father. “As soon as I put it on my back, it felt right,” he says. “I knew then and there that I wanted to share these treasures – that I would open a shop, and my shop would be in Ginza.” In the early 1960s, this was the most fashionable area of Tokyo, a promenade for Japan’s newly affluent consumers. But this was a time before the spread of passenger jets and bullet trains, and Ginza was a world away from the semi-tropical shores of Motoji’s island home. “It took me 13 hours on a ferry, followed by 28 hours on a train,” he recalls, “But I made it eventually.” Ginza Motoji consists of three shops: one for women, one for men, and another that specialises in oshima tsumugi, or kimono from Amami Oshima. Each feels more like an art gallery than a clothing store, exhibiting carefully curated fabrics awaiting purchase and tailoring. A complete kimono, meanwhile, is splayed dramatically, like a soaring bird. The proprietor pulls meticulously boxed rolls of fabric out of storage cupboards and unfurls them on a huge table formed from a single slice of wood cut from a 360-year-old tree. They include works by artisans who have achieved the rank of Living National Treasures: Yuko Tamanaha, who makes ryukyu bingata, an Okinawan style of intricate patterns made using dye-resistant rice paste; Kiju Fukuda, celebrated for his embroidery; and Hyouji Kitagawa, the 18th generation of the family heading the storied Tawaraya workshop in Kyoto’s Nishijin neighbourhood of textile craftspeople – with no male heir, he is probably the last. Almost as if to illustrate the tragedy of a workshop’s demise, Motoji slips on white gloves before touching his most treasured cloth, a simple design of indigo and ivory. The fabric is only 10 years old, but it is already priceless. “Nobody has the skill to make it anymore,” Motoji sighs. “The tradition has been lost.” Every year Motoji invites a selection of his artisans to come to the capital and experience the daily lives of busy, sophisticated Tokyoites. They need to understand their consumers if there is any hope of these endangered skills being preserved for future generations. For this to happen it is imperative that what they make is practical for the modern world. For Motoji, wearing kimono every day means that he now feels uncomfortable in Western clothing. But … Read More

Gen Yamamoto

Gen Yamamoto is a classically trained bartender, though you might not guess it. He has dispensed with many of the rudiments of his profession: he never shakes a cocktail; never stirs with ice in a mixing glass; never makes martinis, negronis or anything else you’ve heard of. And his drinks are usually tiny. At his bar, Yamamoto specialises in omakase courses of original cocktails. Guests choose four or six drinks, discuss their aversions or allergies, and leave the details to him. What he serves will depend on the season, the weather, and the time of day. The cocktails are presented on a lacquer tray, beside a freshly misted seasonal flower. The first soupçon is always refreshing, employing an ingredient such as cucumber juice or ginger. The second has more bite, often using Japanese citrus. And then there’s something more powerful again – perhaps with a fruit tomato, and a gin or shochu. The courses build and build in texture and density, to their dessert-like conclusion. There are many bartenders that show the season in their drinks. They’ll use watermelons in the summer or persimmons in the autumn. Yamamoto takes the idea so much further: having forged ties with farmers, he consults with them about what’s being harvested. He says he’s interested in anything delicious, but is more inspired when the ingredient is a little unusual. He buys lesser-known Japanese citruses, such as hebesu, sumikan or hassaku, and has been known to use fava beans, wasabi, celery root, and fennel. He prepares them more in the manner of a chef than a bartender, simmering reductions, creating compotes, and using copper pans and digital thermometers. Yamamoto devised his first cocktail tasting menu in New York while working as bar manager at Brushstroke, a kaiseki-inspired collaboration between chef David Bouley and Japan’s Tsuji Culinary Institute. “When I moved to America, the ingredients tasted different, the ambience was different, and the environment was different. I started to focus on natural ingredients, at first just mixing them with vodka — a vodka apple martini or something like that. It didn’t work. Each ingredient tasted out of balance. So little by little I changed them.” The mixologist questioned everything he had learned. Why does a cocktail have to be chilled? Why must the elements be integrated? Who says a serving should be 70 millilitres or more? And does the alcohol have to kick so hard? He found Japanese-originated alcohol such as sake or shochu often paired better with his produce than 80 proof spirits. He realised that too much chilling could mute the flavours. And he discovered you can have too much of a good thing. “I make a drink with kumquats, for example,” he says. “If it is a large drink, it’s too thick, too heavy.” His style was taking shape, but Yamamoto couldn’t execute it properly in the U.S. “People there worried more about the speed of service than the quality of the result,” he says. So he moved back home to Tokyo and … Read More

Aritsugu

Kazuo Nozaki is proud that chefs from New York to Stockholm flock to his unassuming shop at the former Tsukiji fish market to purchase high-quality Japanese knives for their kitchens. But famous customers aren’t the reason he starts work at 4am each day. Aritsugu knife shop has been supplying blades to Tokyo fishmongers for more than 90 years. Its main customers are the wholesalers who prepare the early morning tuna, octopus, scallops, and other seafood for Tokyo’s sushi counters and izakaya tables. Starting work long before sunrise, they rely on the shop to sharpen and repair the tools of their trade. Only when this job is done will Nozaki open his shop to walk-in customers, no matter how famous they might be. Tokyo Aritsugu began life in 1919 when, struggling to keep their brood of sons employed, the owners of the famous Kyoto store (est. 1560) dispatched two of their number to Tokyo. They set up shop in the Nihonbashi fish market, later moving to Tsukiji after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Although today both the business and its owner are unrelated to the Kyoto shop, Nozaki’s history with the Tokyo store is long. He came to work at Artisugu to support himself while studying at a Tokyo college. But he put aside his plans for a career in machinery, instead ‘graduating’ to become a master of knives. The child of a fishing family from Kyushu’s Saga Prefecture, Nozaki recalls how, as a boy, he cut soft lead to make sinkers for fishing lines. The only blade he could find to do this was his mother’s kitchen knife. “It was impossible,” he recalls, laughing. “These days, I appreciate the value of having the right tool for the right job.” And so do his customers. The range of knives on display at Aritsugu is staggering. There are knives fashioned specifically for meat, vegetables, noodles and fish; different knives for different fish; and even sets of three or four to prepare just one single species. No self-respecting chef would use the same knife designed to cut off a fish’s head to slice its belly in to sashimi. Nozaki explains that long, narrow ‘willow’ blades for sashimi are popular, as are pointed gyutou – literally ‘beef knives’ – although they can be used for almost anything. Meanwhile the multi-purpose santoku knives, which are rounder at the top and a little wider, always sell out fast. Hand-forged but non-specific in duty, they’re high in both quality and maintenance. Sakai, the traditional sword-making district in Osaka where the knives are made, is a place Nozaki must travel to frequently. There, each blade starts as a dark, dull rod of steel. Heated, hammered and cooled repeatedly for days, it eventually becomes a sharp, shiny instrument of strength and precision. It’s the same technique swordsmiths once used to arm samurai warriors. For casual cooks, alloy and stainless steel knives are more affordable and easier to maintain, although they lack the artisanal commitment of owning a forged … Read More

21_21 Design Sight

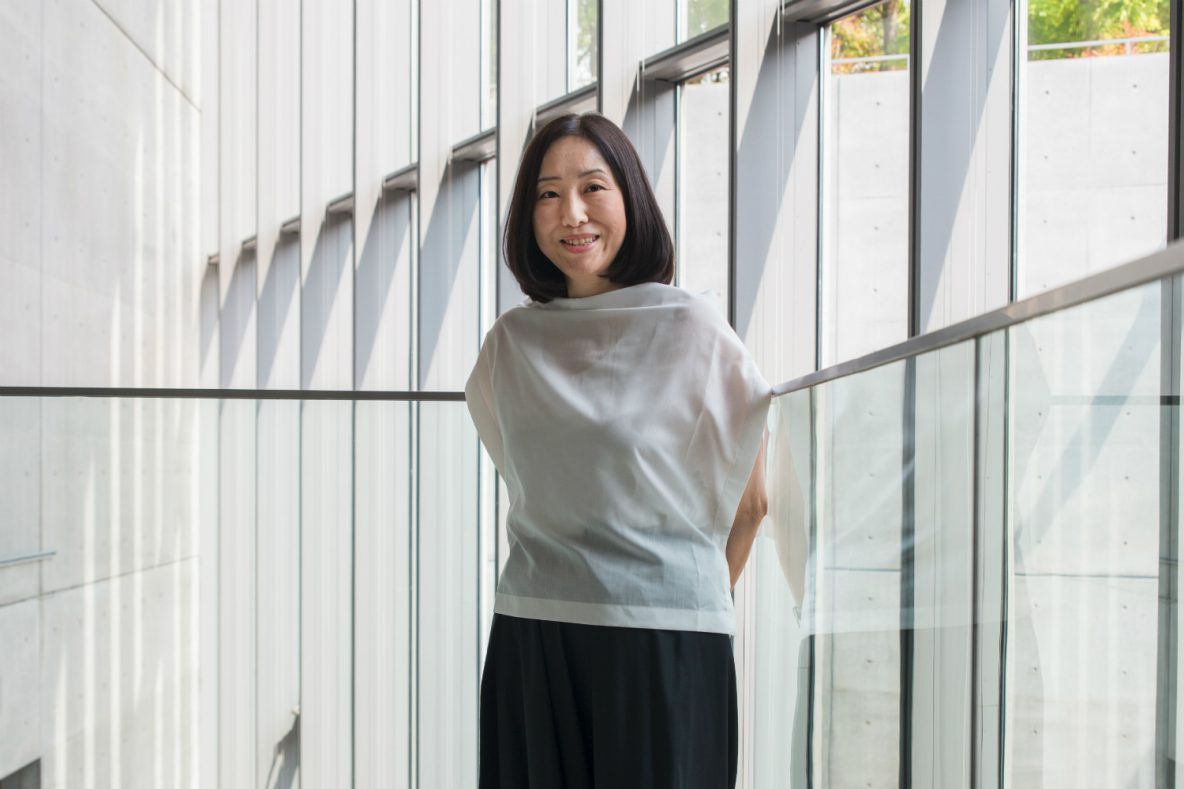

Don’t go thinking that 21_21 is a museum. It can’t be, because it is without permanent collection. But then, neither is it a gallery – its expansive mission is bigger than that. How, then, to explain it? “Most museum and art gallery directors come from the curatorial side,” explains Associate Director Noriko Kawakami. “What’s so special about 21_21 Design Sight is that the directors are all working designers.” They are, in fact, more than that – they are three of the biggest names in the Japanese creative industry: graphic designer Taku Satoh, industrial designer Naoto Fukasawa, and fashion designer Issey Miyake, who has been the project’s driving force from the start. “Another reason we’re different from an art gallery is that we exhibit familiar things from everyday life,” says Kawakami. “But we want to show their beauty and emotion.” During the first half of 2014, Satoh and anthropologist Shinichi Takemura co-directed an exhibition titled ‘Kome: The Art of Rice’, which explored how the humble grain has enriched Japan’s design traditions as well as its diet. A previous exhibition curated by Satoh investigated water, while another by Fukusawa was named ‘Chocolate’. One of Miyake’s motivations has been that, despite its cultural affinity for beautiful and functional things, Japan has no official museum of design – although he never intended for 21_21 Design Sight to become that institution. His is a more modest goal, formulated with the help of late sculptor Isamu Nogichi, architect Tadao Ando, and several others: to create a space where people can experience good design and understand its transformative possibilities. Ando and Miyake collaborated on the structure of the building using the latter’s concept for making garments from a single piece of unbroken thread. Approaching the building through the surrounding gardens, visitors catch sight of two massive triangular roofs at ground level, each made from giant sheets of folded steel. Beyond the entrance, the exhibition rooms are subterranean and surround a sunken courtyard framed by large windows. On sunny days dramatic shadows move slowly across the cavernous space. Kawakami and the three directors meet monthly to brainstorm ideas and choose a curator for each show. For everyone involved, an open mind is imperative: while assisting Satoh in the preparations for ‘Water’, Kawakami says she worked with a scuba diver, an astronomer, a biologist, and other unlikely professionals. “What keeps every exhibition interesting is that each has its own methodology,” she says. “There are never any prepared answers. There are never any rules.”

Sakurai Japanese Tea Experience

Dressed in a spotless white coat, Shinya Sakurai looks every inch the doctor as he slowly measures, heats and pours water into an array of receptacles on the worktop. The object of his intense concentration, however, is not a science experiment, nor are his actions unfolding in a laboratory. Sakurai is, in fact, preparing what is likely one of Tokyo’s finest cups of Japanese tea in a contemporary teahouse. There are perhaps few people who know more about the intricacies, nuances and rituals of Japanese tea than 37-year-old Sakurai, who has devoted the past 14 years of his life to all things tea. It was in 2014 that the mixologist-turned-tea guru opened Sakurai Japanese Tea Experience, first in a space in Tokyo’s Nishi-Azabu neighbourhood, before moving two years later to its current fifth-floor home in Aoyama’s Spiral Building. His goal is simple: in a culture saturated with craft coffee, he aims to reconnect generations of younger Japanese with the increasingly neglected world of tea. “I want to offer people a new way of enjoying Japanese tea,” he explains. “Today, there are so many different teas you can buy in plastic bottles and so many young Japanese have never even tasted a properly prepared cup of tea. I want to change that.” The experience begins the moment customers cross the threshold. The small but perfectly formed space, created by Tokyo design firm Simplicity, is a serene and minimal enclave of clean-lined natural materials, from dark woods to warm copper, complemented by a wall of windows framing an urban skyline. On the menu are around 30 teas sourced from across Japan and loosely divided into three categories: straight, blended (with seasonal ingredients ranging from persimmon to yuzu), or roasted on site by Sakurai in the corner of the tearoom. Explaining the unique qualities of Japanese tea, he says: “Most teas are heated by fire when they are being made, but Japanese tea is made using steam. This makes it a very pure type of tea.” Using an impressive 40 litres a day of hot spring water from southern Kagoshima, Sakurai performs his contemporary take on tea ceremony at an eight-seat counter. And he is meticulous in his preparations. “You have to be very precise,” he says. “Even the slightest change in temperature to the water can change the flavour entirely. For sencha green tea, for example, you must use a lower temperature of water—if it’s too hot, it becomes bitter.” Also on the menu are pretty, bite-sized Japanese sweets (from chestnut yokan jelly to flavour-bursting walnuts and dates in fermented butter), segueing smoothly into tea-inspired cocktails after dark (a refreshing fusion of sencha tea and gin is a typical highlight). Sakurai’s tea-themed tools and accessories are no less eye-catching, from handcrafted tin tea caddies and traditional bamboo ladles to delicately minimal ceramics from Simplicity’s product line S[es]. “The whole setting is very important,” explains Sakurai. “In order to enjoy tea, the atmosphere has to be just right.” Best of all? It’s healthy … Read More